You sit anxiously in the waiting room while your cat undergoes surgery to remove a cancerous mass. Finally, the doctor comes out in his scrubs and tells you he was able to excise the malignant tumor and that he believes he got it all. Relieved but not yet “out of the woods,” you wait for the pathology report. Sure enough, it confirms the surgeon’s belief that he excised the cancer in its entirety. There are clean margins. Why, then, does the tumor grow back in the exact same spot some months later?

“No matter what the shape of the tumor, our aim is always to remove it with a cuff, or margin, of normal tissue all the way around it rather than just shelling it out around the edge,” says Tufts veterinary surgeon John Berg, DVM, and the editor-in-chief of Catnip. “That helps increase the chance that we got the mass in its entirety, with no stray cancer cells or clumps of malignancy at the spot. But the pathologist does not look at the entire tissue that we excise. The lab makes just a few microscopic slides taken from three to five spots. So if the report comes back that the tumor has clean margins — there are no cancer cells in the cuff of normal tissue — it means only that those few spots have clean margins. For most of the tumor, we really don’t know.”

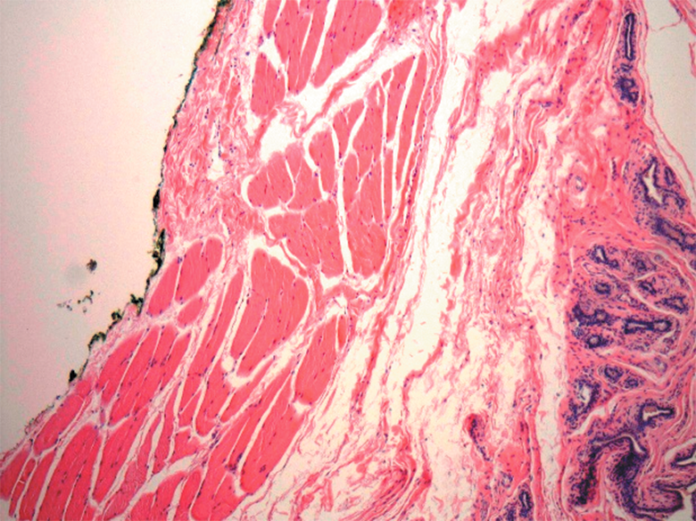

The reason pathologists look only at a few small sections rather than checking the mass all the way around is that there’s no technology for turning the tumor every which way and looking at every last bit of it. You have to cut it into very thin slices — thin enough so that light can pass though in order to be able to see the individual cells under a microscope upon staining. “You would literally need thousands of slices to assess the entire tumor because each slice cuts into the tumor, not just around its surface, ” Dr. Berg says. “It would be cost prohibitive.”

False readings

Another problem is that a pathologist can get false readings — false positives or false negatives. Inside the body, the orientation of normal tissue to cancerous tissue pretty much stays put. But once you remove a mass, tissue can slide around. “Think of a parfait with a layer of yogurt, a layer of fruit, and a layer of granola,” Dr. Berg says. “Some of the granola can jiggle into the fruit, and some of the fruit can migrate into the yogurt.” Likewise, tissue planes can slide, causing cancerous cells to move to where normal cells are, and vice versa, causing a pathologist to get either a false reading of a clean margin or a false reading of an incomplete margin. Research has indicated that about 15 percent of the time margins are deemed clean, the cancer grows back. And several studies have suggested that when margins are pronounced incomplete, the cancer actually doesn’t grow back some 70 percent of the time.

Is assessing margins just a waste of time?

You might wonder why surgically removed tumors are sent to pathologists at all, if assessing margins and predicting cancer recurrence is such an inexact science. The reason is that while margin assessment doesn’t give the whole picture, it’s one of a constellation of factors that can help cat owners determine next steps after the surgery.

One factor is the surgeon’s own assessment. While he can’t see all the cells with the naked eye, he has a sense of how the operation went. “If the pathologist says the margins are incomplete but I felt I got everything, I’ll tell the owner that,” Dr. Berg says. Likewise, he comments, “there are instances in which the pathologist’s report will declare the margins complete, but I feel pretty sure they were not.” That can influence an owner’s decision on whether to opt for radiation — targeted therapy over the area to kill any cancer cells that might have been left behind.

The age of the cat counts, too, Dr. Berg says — how much you’re willing to put your pet through given her age and overall health status. For instance, even if a second surgery might be warranted to go in and scoop out more cancer, it just might not be in the cards. That’s especially true if the tumor is in a spot next to a critical organ like the heart or kidney. Every time you go back in, the subsequent incision has to be larger than the original one, putting the surgeon closer and closer to vital tissue.

The bottom line: assessing margins is part of a multi-pronged assessment that includes both the owner’s own attitude as well as a built-in level of uncertainty. It’s an art as well as a science.