[From Tufts August 2011 Issue]

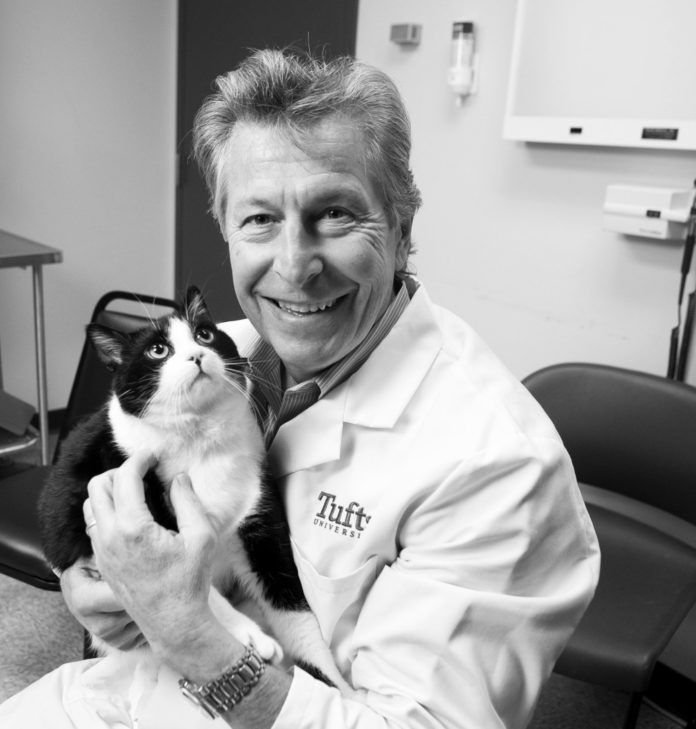

Editor’s note: Nicholas Dodman, BVMS, director of the Animal Behavior Clinic at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, is a renowned animal behaviorist and best-selling author.

ANDY CUNNINGHAM

Many years ago, in the days when I sometimes agreed for logistical reasons to do telephone consultations with distraught pet owners, I found myself talking to a very pleasant-sounding older woman on Cape Cod about her aggressive cat. The cat in question was a 7-year-old cat, the breed of which escapes me now, though the sad tale does not.

The problem, the woman reported, was that her cat would jump up onto her lap, apparently seeking attention, but if she petted him, he would quickly lose patience and bite her hands and arms, inflicting some painful and disfiguring injuries. I was certain I knew what was going on and was happy to issue the advice I thought would help her deal with the problem.

In the veterinary literature, there is a feline behavior problem known as petting-induced aggression, and certainly that term describes the behavior well. The idea is this: A cat initially seeks the owner’s company and attention, but when he tires of being petted, the cat becomes irritable and aggravated, whereupon he uses the language of aggression to arrest the now unwelcome physical contact. The solution voiced by many behaviorists at the time was simply to avoid petting the cat. One behaviorist went so far as to say that cats of this persuasion don’t like to be petted and owners should refrain from petting their cat at all. She qualified this statement by saying that owners of these cats should not be offended by the cat shunning them in this way because the cat probably still likes them, but prefers to show and share affection in other ways.

I was never completely satisfied with the diagnosis of “petting-induced aggression” because it was simply descriptive and didn’t really explain the underpinnings of the behavior. What was it about such cats that made them aggressive in this situation? One day, an owner of just such a cat accidentally filled in what I called my dominance aggression questionnaire for dogs, and lo and behold, there were checks in all of the boxes that would correspond to this type of aggression in a dog. Dominance aggression in a cat, I thought? How could that be?

@ISTOCKPHOTO

From that time onward, I started to ask a lot more questions of owners whose cats bit them and found out that they all displayed a number of other associated character traits and behaviors. For example, they were all fairly pushy and demanding cats. Some were aggressive around their food bowls. Some aggressively guarded favorite objects or resting places. Some would resist postural interventions (including petting). Some would bite their owners in the nose or toe to get them out of the bed in the morning so that they could get fed, and others would sit squarely in front of the person when they were trying to read a newspaper or book. I even had a couple of cats who would bite people if they fell asleep in an armchair as if to tell them to wake up and pay attention instead of dozing off and being lost as company.

The treatment for these bossy cats evolved to be two-fold: Avoidance of further aggression and training the cat to respond to verbal cues so that he could be taught to respond to a voice command in order to “earn” valued resources. The latter, I thought, would teach respect.

In the case of the woman from Cape Cod, I first engaged in the avoidance aspects of the problem and, in particular, taught her how to avoid getting bitten when she was petting her cat. Unlike some of my colleagues, I did not advise her to completely abstain from petting her cat, but rather told her how to read his body language. There was no need for her to prevent the cat from jumping onto her lap and she could even pet him for an abbreviated period of time.

But in the process of doing so, she should pay particular attention to his facial expression, body movements, ear position and any movement of the tip of his tail. Squinty, sideways glances, ears rotating back and tail-tip twitching were all indicators of trouble brewing and were grounds for ceasing petting immediately, standing up and allowing the cat to fall gently to the floor. This she tried as part one of our rehabilitation program — avoidance — but I did not go into the earning resources aspect at that time. A few weeks later, she called me back to report good success. No, the problem was not completely solved, but she had substantially reduced the frequency and severity, and overall, she was very pleased.

The kicker came a few weeks after that when I had a call from her local veterinarian. He reported that the cat was now circling to one side only, and that he had run tests that indicated the cat had a brain tumor. The fact that the cat might have a brain tumor did not cross my radar and was certainly a curveball diagnosis. I’m still not certain that the aggression was caused by the brain tumor, but the fact that she was reporting it to me when the cat was 7 years old as opposed to at a much earlier age should possibly have raised a red flag for me.

The brain tumor was inoperable and the woman made the decision to have the cat put to sleep — so that was the end of the story. I ended up somewhat chagrined that I had not suggested a thorough veterinary exam before offering my behavioral advice. I simply assumed that, as the cat was well at the time of its previous veterinary visit almost a year before, he was still in good shape at the time I offered my advice.

Apparently that was not the case, so while the treatment worked for what I thought was a slam-dunk diagnosis, there may have been a large part of the puzzle that, unfortunately, across the miles was missing to me. I no longer do telephone consultations for that very reason, and in doing any remote consultations through our PETFAX or VETFAX services, I always advise a preliminary veterinary examination and any relevant blood work. I learned from my oversight.