Developed in the late 1940s as a novel tool for examining the internal organs of humans, ultrasound is a technology that uses sound waves to create images of deeply seated, hard-to-reach areas of the body. The technology rapidly gained enthusiastic acceptance among physicians as a uniquely valuable diagnostic aid, and today an estimated 25 percent of all human imaging procedures worldwide employ some form of ultrasound technology.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, ultrasound gradually made its way into the world of veterinary medicine. And in the past two decades, its use has become a routine, if not essential, service offered by private veterinary practices as well as referral clinics and teaching hospitals.

Thinkstock

Certain advantages

Ultrasound has several clear advantages over other imaging methods, notes Olivier Taeymans, DVM, assistant professor of radiology at the Cummings School. Among these advantages, he points out, is the fact that an ultrasound procedure — compared to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scanning — is very speedy. “Depending on the skill of the clinician,” he says, “a full abdominal ultrasound scan of a cat can be done, on average, within a half-hour.”

Furthermore, he adds, “We can do an ultrasound exam on patients that are awake, whereas MRI and CT require general anesthesia or, at least, very heavy sedation, which can be dangerous for some animals.” Moreover, ultrasound — unlike radiography and CT scanning — does not require the patient to be exposed to X-rays, which, Dr. Taeymans points out, “are potentially harmful to both patient and doctor.”

Another advantage is that an ultrasound examination is relatively inexpensive, largely attributable to the fact that the apparatus required for this technology is far less costly than the equipment needed for other imaging techniques.

In general, says Dr. Taeymans, “Animals tolerate the procedure pretty well. It’s not scary. It takes place in a dark, quiet environment, where the cat is basically lying on his back on a trough-shaped table and getting a belly rub.”

Keeping the cat comfortable

During CTs and MRIs, it’s critically important that the animal is absolutely still, but in an ultrasound exam, it’s okay if the cat moves. You just wait a little while until the animal gets back into position, and then you simply rescan the area.”

An ultrasound session typically requires only two people — an animal handler, who holds the patient in position, and a radiologist, who does the scanning. Once in the examining room, the animal is placed on a table and the hair on his belly is clipped short. The cat’s smooth abdomen is then coated with a slippery gel, which enables the probe to glide smoothly across the animal’s skin and make full contact with the area under examination. For a brief period — rarely longer than 20 or 30 minutes — the probe is run across the target area. While the sonographer studies the visual images on the monitor, the assistant will soothingly stroke the animal to keep him as still and comfortable as possible.

A typical ultrasound scanning device is made up of three main components — a probe (transducer); a central processing unit (CPU); and a display monitor. First, the CPU transmits electrical energy to the probe. Next, the probe emits high-frequency sound waves — well beyond the range of human hearing. These ultrasonic waves are directed at the target organ and receive the waves that rebound from it. The reflected waves are transmitted back to the CPU as data in the form of electrical current, and the CPU instantaneously assembles this information to create a visual image — the sonogram — that appears on the display monitor. (The image can also be transferred electronically to a hospital archive for later viewing.)

Because it is responsible for emitting and receiving the ultrasonic waves, the probe is regarded as the core of the ultrasound configuration. Probes typically resemble thick pencils that have wedge-shaped sensing mechanisms at their tips.

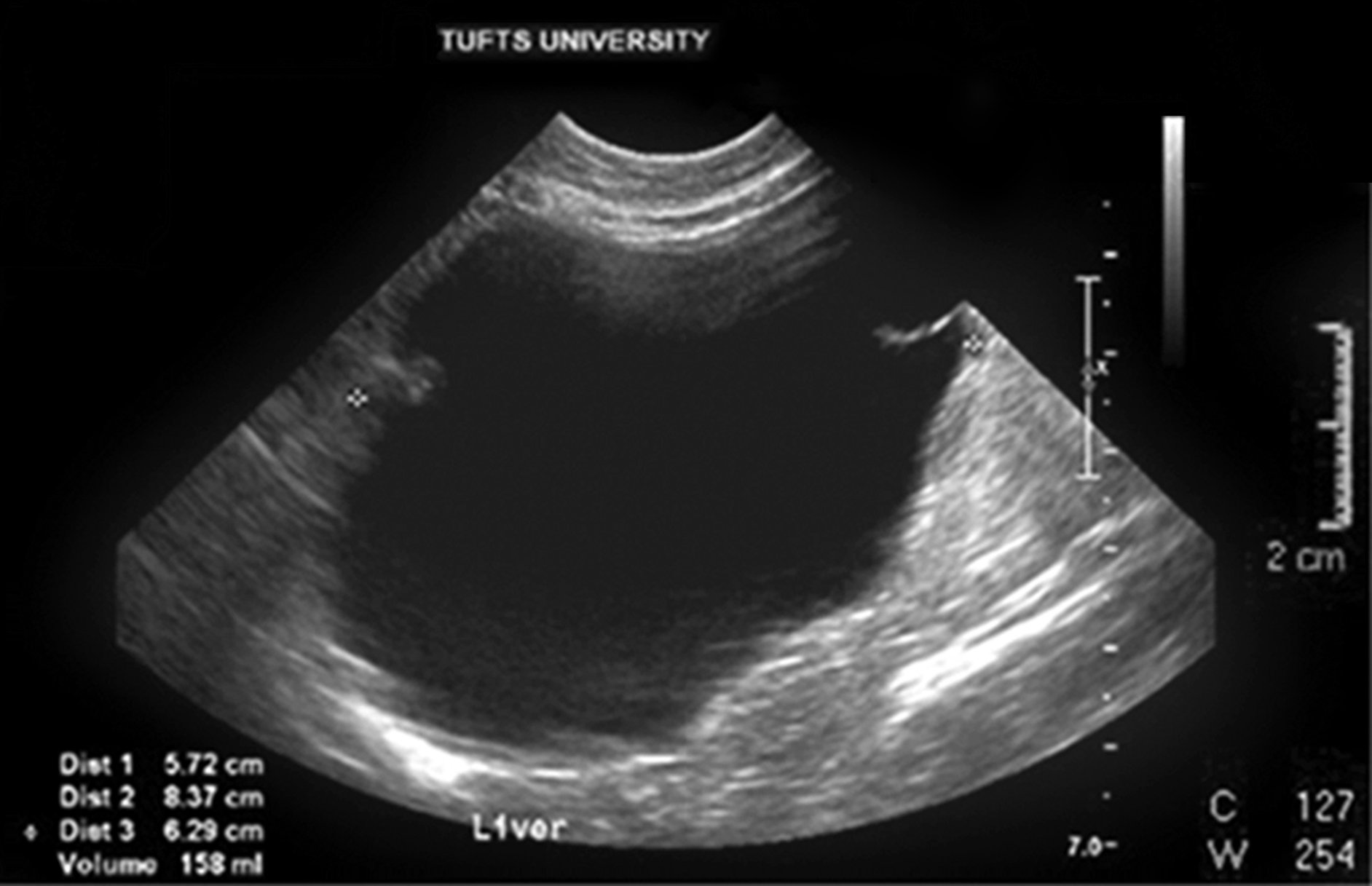

To the untrained eye, an ultrasound image is likely to be perceived as nothing more than a mottled field of blacks, whites and shades of grey. To an experienced veterinarian, however, the image can provide a wealth of information about the liver, kidney, uterus and other internal organs. Ultrasound also is commonly used to view the structure and function of an animal’s heart. Whereas X-rays are used to study bones and other solid structures, Dr. Taeymans points out that ultrasound is very good for looking at soft tissues. By studying the various shades of gray, a radiologist can tell, for example, that there are lumps on an animal’s liver.

Although the images will not reveal precisely what kind of lumps they are, the procedure will reveal that they are present and should be further evaluated. Soft-tissue disorders that ultrasound can detect include intra-abdominal tumors, enlarged lymph nodes; abnormal blood vessels; pancreatitis; uterine infections; and many other conditions. The technology also is widely used to confirm pregnancy and to assess the health of fetuses. However, ultrasound is virtually useless for some applications, says Dr. Taeymans. For example, he points out that the technology is incapable of peering beneath the outer layer of the lungs, because ultrasound waves cannot penetrate the air in the lungs, or of penetrating beyond the exterior surface of bones.

Highlights abnormalities

“This is a very sensitive technology,” he says. “With ultrasound, we’re very good at picking up abnormalities. The images will easily reveal whether a tissue has an abnormal texture. An abnormal area in the liver, for example, may look somewhat darker or brighter than surrounding tissue. We can tell that there’s something abnormal, although what we’re seeing is so nonspecific that we may not know what precisely is wrong with the tissue. But the ultrasound image points us in the right direction.”

A subsequent diagnostic procedure may also employ ultrasound, he adds: “The imaging can guide us in the process of extracting cells or tissue from an internal organ so that we can do a biopsy.”

The efficacy of ultrasound as a diagnostic mainstay for veterinarians has by now been well established, Dr. Taeymans observes. “In more than half of the cats that undergo ultrasound,” he says, “we do not need further diagnosis. Maybe we’ll have to inject a needle into a tissue to get a sample, but in most cases this is not necessary once we’ve done the ultrasound. Usually we’ll create a list of possible disorders based on our review of the ultrasound image and give this list to a clinician. The clinician will then try to rule out some of these possibilities by reviewing the patient’s presentation, medical record, prevalence of the disorder, breed disposition, and other factors, and will start treatment from there. In some cases, we may need to refer to another imaging modality, such as MRI or CT — but these cases are very rare.”

Ultrasound equipment is increasingly being used in private veterinary practices. “The cost of an abdominal ultrasound examination,” Dr. Taeymans notes, “will typically range somewhere between $250 and $350. The procedure may be less expensive if the veterinarian is looking at a specific joint or a small, very targeted area — but the bulk of the applications for this technology will involve imaging of the entire abdomen.” — Tom Ewing