A few decades ago, recommendations regarding feline vaccinations were relatively simple. Veterinarians generally agreed that all domestic cats should be inoculated annually with a number of vaccines. In recent years, however, the issue has become far more complicated and in some respects more controversial.

Thinkstock

Back in the early 1990s, only four or five vaccines were available; today, no fewer than 10 vaccines have proven to be generally effective in providing a cat with immunity against a wide variety of feline diseases. And although the vaccine safety and efficacy record overall is very good, it has now become clear that vaccines can damage developing fetuses and stimulate serious allergic reactions in some cats.

Also of some concern is the potential development of a cancerous growth — called a vaccine-associated sarcoma — that in rare instances can develop at the point on a cat’s body where a vaccine has been injected.

Vaccinations rethought

Consequently, opinions have shifted over the years regarding the frequency with which some vaccines should be administered and how often booster shots should be given. Research has brought into question, for example, the need for cats to be routinely revaccinated on a predetermined schedule — yearly, say, or every three years. Certain laboratory tests may reveal that, as the result of a previous vaccination, the antibody levels in a cat’s blood remain high enough to protect her against a specific virus. In that case, the animal would theoretically be protected against disease associated with that virus, and a booster shot would not be necessary.

By skipping a booster shot, the cat would be spared the potential health risks that accompany vaccination, and her owner would be spared the unnecessary expense of the procedure.

These and other considerations eventually prompted veterinarians in the late 1990s to reexamine their approaches to feline vaccination. A series of subsequent reports from the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) and other veterinary organizations produced a general consensus among practitioners on several broad issues. Currently, says Orla Mahony, an assistant professor in the department of clinical sciences at Tufts, the vast majority of veterinarians follow the AAFP guidelines.

Among its underlying principles, the organization strongly believes that (1) feline vaccination should be regarded as a complex medical procedure and should therefore be undertaken with correspondingly serious consideration; (2) no vaccine should be considered as always safe and always successful in preventing infection; and (3) no vaccines are always appropriate and, therefore, their necessity for individual cats should be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Thinkstock

In line with these principles, AAFP published in 1997 its first set of feline vaccination guidelines, developed by an international team of experts in veterinary immunology, infectious disease, and internal medicine and endorsed by a panel of veterinary practitioners. In general, the guidelines authoritatively recommended that the overall objectives of vaccination should be (1) to vaccinate the largest possible number of animals in the population at risk for a specific disease; (2) to vaccinate only against infectious agents to which a cat has a realistic risk of exposure and subsequent development of disease; and (3) to vaccinate each animal no more frequently than is necessary.

Periodic updates

Since its initial set of recommendations, AAFP has periodically issued updates reflecting advances in veterinary research and practice, the latest of which was published in October 2012. These updates, however, remain consistent in the recommendation that individual cats be given only the vaccines from which they can clearly benefit and that they receive the vaccines only as frequently as necessary to protect them against a specific disease.

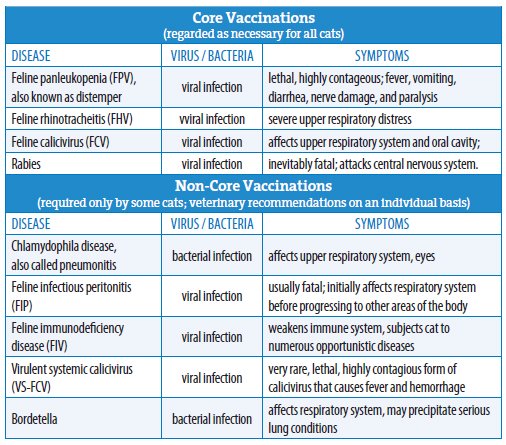

All vaccines that the AAFP recommends in its latest set of guidelines have, through rigorous testing, proven to be largely effective in protecting cats against serious infections. Four of the 10 currently available vaccines are referred to as “core vaccines,” while the remaining six are considered “non-core.”

Core vaccines: mandatory

“The core vaccines,” explains Dr. Mahony, “are those that are regarded as necessary for all cats, while the non-core vaccines are required only by some cats, with recommendations for their use being made on an individual basis.”The core vaccines cited by AAFP offer protection against the following viral infections:

- feline panleukopenia (FPV), a lethal, highly contagious disease, also known as distemper, that is marked by fever, vomiting, diarrhea, nerve damage, and paralysis;

- feline rhinotracheitis (FHV), a herpesvirus infection causing severe upper respiratory distress;

- feline calicivirus (FCV), an infection of the upper respiratory system and oral cavity;

- rabies, an inevitably fatal disease caused by a virus that attacks the central nervous system.

For FPV, FHV and FCV, the AAFP recommends that all kittens be initially vaccinated at six weeks of age and receive booster shots every three to four weeks after that until they are about 16 weeks old. (This is called the “kitten series.”) Another revaccination should be administered one year following the initial vaccination, and booster shots should be given every three years thereafter.

In addition, the latest AAFP recommendations advise that a vaccine to prevent infection with the feline leukemia virus (FeLV) be considered a core vaccine for kittens. It should not be started before a kitten is eight or nine weeks of age — preferably between the ages of 12 and 16 weeks — with revaccination administered two to six weeks after the initial dose in order to ensure protection against the virus. Another revaccination should be given at one year of age but no more frequently than once every three years thereafter.

Rules on rabies

According to the latest AAFP guideline update, an initial rabies vaccination should not be given before a kitten has reached the age of 12 weeks, after which another vaccination should be given within one year, with additional booster shots administered annually thereafter. (Because rabies can be transmitted from an infected animal to a human, annual rabies vaccinations are required by law in most U.S. locales.)

Non-core: as necessary

The remaining six available vaccines are categorized as non-core. Their use should be determined by a veterinarian on a case-by-case basis depending on a number of variable factors, such as an individual cat’s age, overall health, lifestyle, and environment. In addition to FeLV, a gravely serious infection that is known to directly or indirectly cause several feline diseases, such as lymphosarcoma, the non-core vaccines include those that protect against:

chlamydophila disease, an acute bacterial infection, also called pneumonitis, that affects a cat’s upper respiratory system and eyes;

feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), a usually fatal viral disease that initially affects the respiratory system before progressing to other areas of the body;

feline immunodeficiency disease (FIV), a viral infection that weakens a cat’s immune system and subjects the animal to numerous opportunistic diseases;

virulent systemic calicivirus (VS-FCV), a very rare but lethal and highly contagious form of calicivirus that causes fever and hemorrhage. This virus is usually found in crowded feline environments, such as shelters; and

bordetella, a bacterial disease affecting the respiratory system that may precipitate serious lung conditions.

Determining which cats should be immunized against the non-core diseases, at what age, and how often continues to be the subject of debate. Following are some of Dr. Mahony’s views regarding factors that should be taken into consideration regarding administration of a vaccine:

“The age of a mature cat would not be a factor, but you wouldn’t vaccinate a cat who is less than four or six weeks of age.”

“You should not vaccinate a pregnant cat unless she is in an extremely high-risk environment, such as a shelter, since any vaccine would have the potential for infecting a fetus and causing congenital disease.”

“Indoor-only cats generally require fewer vaccines. You would certainly give them all of the core vaccines, but not necessarily the non-core vaccines. However, indoor-outdoor cats should receive all of the core vaccines and some or all of the non-core vaccines.”

“If your cat’s immune system is suppressed — if it is FIV- or FeLV-positive or has cancer, for example, and is being treated with chemotherapy — you should probably hold off on vaccinations until the animal is no longer being given medications to treat those disorders.”

One risk to beware

Most serious among all risks associated with the use of disease-preventing inoculations, Dr. Mahony points out, is the remote possibility that a cat would develop a cancerous tumor called injection-associated sarcoma. This disease is now extremely rare; studies indicate that it occurs only in about three of every 10,000 vaccinated cats. Treatment requires wide surgical removal, and the tumor can spread to distant sites and be fatal. The only way in which to prevent its occurrence, Dr. Mahony points out, would be to avoid vaccinations entirely, which would be unwise.

The best way to minimize the risk for injection-associated sarcoma, she says, is to restrict the number of injections that a cat receives during her lifetime. Rather than having an animal receive periodic injections of all available vaccines, she advises, consultation with a veterinarian can yield a vaccination plan that is likely to reduce the number of injections the animal receives and, consequently, her risk for vaccine-associated sarcoma.

“We recommend that there be no set vaccination schedules that call for every cat to be vaccinated similarly,” says Dr. Mahony. “All cats should be treated as unique individuals. They all have different requirements.” — Tom Ewing