Because cats are so incredibly nimble and graceful, we tend not to think of them as vulnerable to the pain of osteoarthritis, a disease characterized by worn-down joint cartilage. But research has suggested that 90 percent of cats develop signs of arthritis over time, with some 45 percent — almost one in two cats — experiencing pain as a result.

It might be hard to tell. We often attribute a slowdown in feline activity to the aging process rather than to pain. Then, too, we frequently assume a pet will reveal arthritis pain with a limp. But cats rarely limp from arthritis; that’s a dog thing. To make an assessment more difficult still, cats are good at keeping their pain hidden — a holdover from when their ancestors needed to put a face on any bodily discomfort in order to fool potential predators into thinking they could put up a fight or run away fast. The lack of recognition of arthritis pain in cats is severe enough that by one estimate, less than 1 percent of cats with arthritis pain are seen by veterinarians.

That’s a lot of pain untended to. When the arthritis process takes hold, the soft, spongy cartilage that normally keeps two bones from touching wears away. That, in turn, causes the bones to scrape against each other as they move, and the ensuing pain can be severe. (It’s true for people with arthritis, too.)

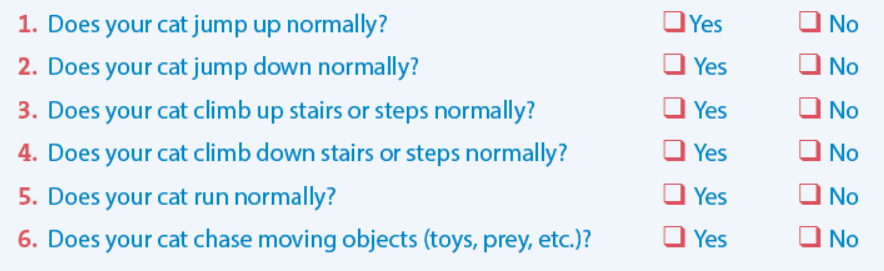

Now, researchers at North Carolina State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine have come up with a 6-question survey with simple “yes” or “no” answers that cat owners can answer in less than a minute to see if their cat might have arthritis and then, if necessary, take their pet to the doctor for a work-up.

How researchers developed the 6 relevant questions

To come up with the survey, the scientists looked over five previous studies on more than 300 cats — about 80 percent of them with painful arthritis and 20 percent without. Comparing answers about behavior from owners who knew their cats had arthritis to the answers of owners who were unaware of their cats’ condition, they were able to come up with a list of six identifying signs. (Questions pertaining to changes in a cat’s use of the litter box or how often she vocalizes were dropped, as they were deemed not specific enough to arthritis pain.) The culmination of the North Carolina State University research is the Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Checklist.

A “yes” answer to even one or two of these questions should prompt a visit to the veterinarian. It doesn’t automatically mean your cat has arthritis pain, but there’s a reasonably strong chance. A veterinary visit in response to “yes” answers will also help generate a discussion about how long ago the deterioration in activity started and to what degree it appears to have progressed. The vet might also ask about the cat’s sociability and emotional well-being, wanting to find out whether the pet hides more or prefers to be by herself more often. Answers to those questions can yield further clues. A cat in pain may simply not be herself and not want to interact.

*Developed by veterinarians Masataka Enomoto, B. Duncan X. Lascelles, and Margaret E. Gruen at the College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University.

The checklist does not by itself stand in for a medical diagnosis. The veterinarian still has to examine the cat and take x-rays before embarking on a treatment plan. But the questionnaire has been verified to have remarkable sensitivity and specificity and would tag more than half of cats suffering from arthritis pain that otherwise might have gone unnoticed. The questions are so targeted toward arthritis pain, in fact, that even if you don’t have stairs in your home and therefore can answer only four of the questions, it will not downgrade the questionnaire’s screening ability. The questionnaire makes a terrific “starting point for discussion…and further veterinary investigation,” the investigators say in the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, where they published their research.

It’s also an important questionnaire because it addresses issues that the vet is not going to be able to assess at the office, where a cat is likely to be scared and out of sorts and not interested in jumping onto a counter or chasing a toy. That is, it provides the veterinarian with information that she can then use to inform her professional assessment, which in addition to x-rays will likely include testing for decreased range of motion in the limbs, and checking for joint pain by palpating (feeling) the limbs during a clinical exam.

Once arthritis is diagnosed

If it turns out your cat does indeed have arthritis, there are a number of effective tools in the treatment arsenal. For one, the doctor can prescribe pain killers, often in the form of anti-inflammatory drugs. The vet may also recommend supplements with glucosamine and chondroitin — cartilage-protecting agents. Also, if your cat is overweight, she can help get your pet on a good weight management plan; excess weight is second only to advanced age as a cause of arthritis. The additional pounds put extra pressure on joints that might already not be in the best shape, and losing even just a few pounds can often confer significant pain relief.

Finally, the veterinarian will help you determine the right amount of moderate exercise. It may seem like a cat with diseased joints should just take it easy, but moving around by chasing a beam of light or wrestling with a food puzzle gets oxygenated blood and nutrients into the joints. It also builds up the muscles around the joints and allows them to serve as shock absorbers so the joints don’t have to perform that function.

In reading the section Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Checklist*: I believe that you did not mean to say “if “yes” answer to even one or two of these questions should prompt a visit to the veterinarian.”

I answered “no” to all of the questions as my Siamese has had both hips broken in an accident and he has no hip ball joint. So he can’t jump normally, climb stairs normally, run normally, or play with his toys normally (whatever that means). He has been under veterinarian care since he was rescued in 2011.

If I am reading this correctly, if I answered yes to those questions, then he wouldn’t need veterinarian care for arthritis (as this is my interpretation).

I think the writer of the article got yes and no mixed up.

I agree with Frank!

Please let readers know if the ‘Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Checklist’ been corrected. Thanks!

Can you give a cat wild lettuce or ghost pipe for arthritis pain?

Note to Tufts Catnip: Is the chart correctly displayed now? Yes or No? Please respond to the earlier comments. Thank you kindly.

Why have you not corrected your article? Many others have already pointed out that “Yes” responses do not indicate an issue with arthritis. You compromise the integrity of your organization and publications by leaving this unattended for almost a year now!

As a human with arthritis I can tell you that an old injury to a joint almost always leads to arthritis.