Perhaps you’ve seen television footage of surgeons talking about preparing for the separation of conjoined twins by practicing the operation on 3D models that show where the babies are attached. That allows them to get the best handle on how to do it without severing critical blood vessels or cutting into vital tissue at the wrong place during the actual surgery. They can practice over and over until they are confident they will secure the best outcome with the least risk, also using computer renderings to help in the effort to “see” the problem. Veterinarians are now beginning to use 3D models, too, and the technology has come to the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University.

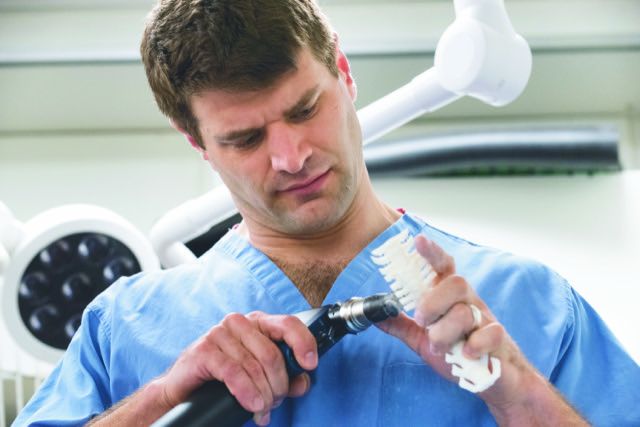

Board-certified orthopedic surgeon Mike Karlin, DVM, heads up the lab at the Tufts veterinary hospital that creates 3D models and uses them himself, mostly to help correct anatomical deformities in animals. “I’ve used this technology to stabilize the spine of a cat that was not aligned correctly,” Dr. Karlin says. “With a computer model, I was able to visualize the position of the screws that would be necessary to the realignment and allow the cat to have better mobility. We average 3D modeling four to six times every month to prepare for a procedure.

“There are so many ways you can use 3D modeling,” Dr. Karlin comments. “The majority of what you can see on a CT scan I can recreate in 3D — it could be a liver mass or a set of bones or an abdominal cavity. And not just for cats and other typical pets. I did a tortoise shell that had a hole in it so the vets at Tufts who heal exotic animals could explain to students about shell repair in a mock operation. It’s amazing because it allows you to troubleshoot a procedure ahead of time until you get it where you need it to be. Then, when the animal is on the table, you already know what you’re going to come across and what you’ll have to do — and how. You still have to make adjustments and judgment calls during the surgery, but the models go a long way in cutting down on unknowns.

“A lot of what I use it for is to correct orthopedic deformities,” Dr. Karlin says, “but its applications are limited only by our knowledge about how it can help. As the field grows, our understanding about how it can improve outcomes for cats and other animals will increase.”

How the models are made

People involved in making 3D models call it 3D printing, but “printing” is a relative term. The models are made from any of a number of materials, with the ones at Tufts composed with resin that is reminiscent of a hard plastic.

It all starts with a CT scan or MRI. The picture, which is comprised of multiple “slices” of imagery to create 3D images, is then “plugged into” software on a computer that instructs the printer to create the actual model. “It’s computer language that makes it happen,” Dr. Karlin says.

It doesn’t occur in a few seconds, the way a piece of paper flies out of a regular printer. Depending on the bone or series of bones or organs or other tissue, the printer might be able to make the model in as little as 6 hours, but in some cases it can take 24 hours. If it’s very complicated it might take 36 hours. You can watch the layers of resin forming and “growing” on a platform through transparent plastic on the front of the “printer,” which looks kind of like a mix between a very cool microwave oven and a futuristic bread-making machine.

For an orthopedic surgeon like Dr. Karlin, there’s an interplay between the 3D resin models created in the machine and the renderings on the computer. “You get the CT scan and from that scan go on to ‘print’ a bone, or bones, associated with a deformity,” he says, “but then you make guides with the help of software that allow you to cut the bone virtually [on the screen] in order to reduce the deformity. The software allows you to manipulate the area of interest to show you what will happen when you cut and move the bone. It’s a way of rehearsing the surgery in the computer to see how things will look once they are corrected. Then you can practice the surgery on the 3D model itself before operating on the actual animal. If you mess up on the model or the cutting doesn’t work out the way you anticipated, you can just make another model.”

Used in teaching

One of the bonuses of 3D modeling, Dr. Karlin says, is that it can be used not only for patients but also to teach Tufts veterinary students no matter what animal they are studying. If someone can actually see a problem and watch what it takes to correct it, they get a much better learning experience than if it is simply explained in a lecture. What better way to visualize anatomy, Dr. Karlin says, than to hold it in your hands? It feels very realistic.

Veterinary students are now practicing spay surgery using a combination of 3D models and simulated organ structure, so that when it comes time to perform a spay on an actual pet, they already have some familiarity with the procedure. The technology is only expected to spread and improve going forward..