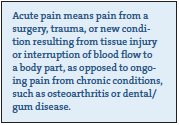

Were you aware that in people, inadequate treatment of pain following procedures like C-sections and chest surgeries can pave the way for chronic pain that lasts long beyond the recovery period? The same is true for cats. It’s because neurological and chemical pathways in the body that relay messages of pain to the brain become sensitized if pain is not adequately controlled from the start, making it easier for pain sensations to keep reoccurring.

There’s a medical term for failing to recognize and adequately treat pain: oligoanalgesia. And too many cats fall victim to it.

That’s not to say veterinary medicine hasn’t made significant advances in recognizing and treating acute pain in cats. It has. There are now validated pain assessment tools that take into consideration a cat’s body posture and facial expressions. You probably know yourself by this point that if your cat’s head is hunched below her shoulder line or her whiskers are straight out rather than curved downward, she may be feeling significant pain.

Furthermore, more and more veterinary practices have started to administer pain relievers before surgical procedures to get out in front of any post-operative pain, just as is done for people. And veterinarians no longer rely on information extrapolated from research on dogs and apply it to cats when it comes to which pain relievers to use and in what dosages. The published scientific literature on cats themselves has really grown.

Yet significant gaps in pain treatment remain, say the 2022 Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Acute Pain in Cats published by the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM). Pain assessment is still not performed enough in the clinical setting, the organization reports. And many veterinarians do not administer or prescribe analgesics to be given to cats at home after routine hospital procedures such as neutering. Your cat might end up an unintended victim of these types of oligoanalgesia, not only if she undergoes a surgical procedure but also in the event of other in-stances where she might have acute pain, such as after a fall or if a tooth has cracked.

Management of Acute Pain in Cats published by the International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM). Pain assessment is still not performed enough in the clinical setting, the organization reports. And many veterinarians do not administer or prescribe analgesics to be given to cats at home after routine hospital procedures such as neutering. Your cat might end up an unintended victim of these types of oligoanalgesia, not only if she undergoes a surgical procedure but also in the event of other in-stances where she might have acute pain, such as after a fall or if a tooth has cracked.

The more a cat’s pain is untended, the worse things get. The ISFM points out that “each painful procedure a cat undergoes can have an additive effect,” meaning the pain keeps piling on.

To make sure your cat does not become subject to oligoanalgesia, take the following steps.

- Ask your vet how she assesses and manages pain. There are three validated assessment tools for acute pain in cats. One is called the UNESP-Botucatu Multidimensional Feline Pain Assessment Scale, and it looks at such things as a cat’s posture, activity, attitude, and reaction to being touched. Another is the Glasgow Composite Pain Scale for Felines, which checks vocalizations, ear position (ears flat out to the sides are a sign of pain), and responses to interaction with an observer, in addition to other signs. The third is the Feline Grimace Scale, which looks at how “tight” the eyes are as well as muzzle tension and whisker and head position.

It is not absolutely critical that your vet uses one of these scales. But you should be able to come away from a conversation with your cat’s doctor comfortable that pain management is integral to her practice.

- If your cat has to stay in the hospital, it’s best if she can be in a quiet and comfortable area away from dogs, perhaps with a box in her cage so that she can snuggle inside or perch on top — whichever would make her feel less stressed. If at all possible, your cat should also have a comfortable bed and a spot where she can go and not be seen by people or other cats. Furthermore, in the best-case scenario, all handling by clinic personnel will be gentle. Pain relief is not just about correct usage of drugs. It’s about an environment conducive to healing. Think of yourself if you have a migraine or perhaps a very bad cold. You don’t just need medicine. You might need a darkened room away from all the other activity in the house so you can rest comfortably and with the knowledge that you will not be interrupted.

- Keep in mind that you are on the front lines of your cat’s pain management and want to avoid oligoanalgesia yourself. Talk to your cat’s doctor about what pain-relieving prescriptions she might need for you to administer when you take her home. Tufts veterinary pain management specialist Alicia Karas, DVM, says that “With each pain management plan, it is important that the owner be given specific instructions, both verbally and in writing, including when the next assessment is recommended. As treatment progresses and pain control improves, modifications to instructions should be made clearly and in full consultation with the owner. It is also important that owners be made aware of potential adverse drug effects and of the action to take if these are seen. Especially for cats, technicians should provide a hands-on demonstration on how to administer medications and handle the pet at home.”

Compliance will improve, Dr. Karas says, if the pet owner understands the treatment schedule and a demonstration is given. The client should also be encouraged to address concerns about their pet’s condition and treatment plan via email, phone, or follow-up consultations.

- Back at your house, give your cat a comfortable and quiet area to sleep or just rest. She also should have a place to hide (as always) and easy access to her food, water, and litter box if she is having trouble moving about. Additionally, other pets and small children should be kept away from her if they are going to interfere with her sense of security.

- Look for signs of pain on your own and call the doctor’s office if you think the analgesics she has been given are not doing enough. Such signs include being hunched over, not wanting to eat, not wanting to be touched or interacted with, and not being able to stretch out or curl up comfortably. Your cat may also be telling you she’s in pain if she’s immobile, grouchy, stiff, hiding, or has a drooped ear position or squinting eyes.

Long ago, we got an adult cat, my mom got him fixed-then afterwards he sat funny-all hunched up.

My male 9 year old began to suffered with acute sinus infections. Otherwise his health was good. The vet was never able to figure out why it happened over and over. Any idea why this would occur in a cat?

He would come to me and bury his face in my palm when it hurt. The meds became so strong, it got to the point it made him not want to eat. We eventually let him pass on he was just suffering.